Best of Monteverdi Choir

Best of Monteverdi Choir

Led by conductor Jonathan Sells, the Baroque choir present a dazzling showcase of their repertoire.

The Monteverdi Choir and the English Baroque Soloists have been at the cutting edge of historically informed performance since their foundation over 60 years ago. With esteemed Baroque conductor Jonathan Sells – himself a former Monteverdi singer – at the helm, the Monteverdi Choir showcases enthralling works from their repertoire.

The performance opens with Purcell. Heard at every royal funeral service for the past three hundred years, Henry Purcell's deeply moving Funeral Sentences is a poignant musical expression of the sorrow and dignity surrounding death.

Closing the concert is George Frideric Handel'sspectacular Dixit Dominus, a tour-de-force of the choral repertoire that showcases both the 22-year-old composer's utter mastery of the form and the assembled musicians' facility with its dramatic and technical demands.

This concert will be recorded for broadcast by our partners BBC Radio 3. Find out more.

breathtaking

Listen on Soundcloud or Spotify.

Supported by Dunard Fund

Programme

Sung in English, German and Latin with English surtitles.

A keepsake freesheet is available at the venue for this performance.

Full programme

Purcell Hear my prayer, O Lord

2minsPurcell Funeral Sentences

15minsII. Man that is born of a woman

III. In the midst of life we are in death

V. Thou knowest, Lord, the secrets of our hearts

JS Bach Der Geist hilft unser Schwachheit auf, BWV226

8minsJohann Christoph Bach Ach, dass ich Wasser gnug hätte (Lamento)

8minsJS Bach Singet dem Herrn ein neues Lied, BWV225

13minsI. Singet dem Herrn ein neues Lied

II. Wie sich ein Vater erbarmet

III. Lobet den Herrn in seinen Taten

Purcell Jehovah, quam multi sunt hostes mei, Z.135

7minsHandel Dixit Dominus

34minsI. Dixit Dominus

II. Virgam virtutis tuae

III. Tecum principium in die virtutis

IV. Juravit Dominus

V. Tu es sacerdos in aeternum

VI. Dominus a dextris tuis

VII. Judicabit in nationibus

VIII. De torrente in via bibet

IX. Gloria Patri, et Filio

Performers

CloseOpen

- Monteverdi Choir

- English Baroque Soloists

- Jonathan SellsConductor

- Zoë BrookshawSoprano

- Chloë MorganSoprano

- Reginald MobleyCountertenor

- Hugo HymasTenor

- Florian StörtzBass

Monteverdi ChoirCloseOpen

- SopranoZoë Brookshaw

Chloë Morgan

Rachel Allen

Eloise Irving

Lucy Knight

Charlotte La Thrope

Emily Owen

Theano Papadaki

Rebecca Ramsey

Cressida Sharp - AltoReginald Mobley

Francesca Biliotti

Sarah Denbee

Annie Gill

Hamish McLaren

Tim Morgan - TenorHugo Hymas

Rory Carver

Thomas Herford

Tom Kelly

Edward Ross

Will Wright - BassFlorian Störtz

Robert Davies

Tristan Hambleton

Jack Lawrence-Jones

Thomas Lowen

George Vines

English Baroque SoloistsCloseOpen

- ConductorJonathan Sells

- ViolinBojan Čičić

Sarah Bealby-Wright

Guy Button

Davina Clarke

George Clifford

Will Harvey

Will McGahon

Sophia Prodanova

Rachel Simpson

Rachel Stroud - ViolaThomas Kettle

Joanne Miller

Sagnick Mukherjee

Dan Shilladay - CelloRuth Alford

Pedro da Silva

Felix Knecht - Double BassKate Brooke

Rosie Moon - BassoonPhilip Turbett

- OrganJames Johnstone

- HarpsichordPaolo Zanzu

- TheorboPablo FitzGerald

Dive Deeper

Listen to The Warm Up: your audio introduction to the performance.

Programme Note

By Joanna Wyld

Joanna Wyld regularly writes for the BBC Proms, Salzburg and Cambridge Music festivals, the Barbican, Southbank Centre and Wigmore Hall. She has given pre-concert talks at the Queen Elizabeth Hall and Royal Festival Hall and wrote the libretto to Robert Hugill’s opera The Gardeners.

Sacred Expression

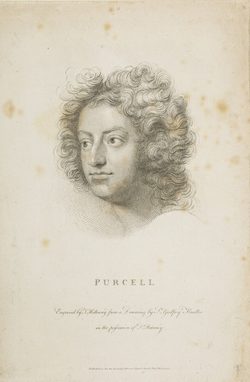

Between the late 1670s and his death in 1695, Henry Purcell wrote some hugely expressive sacred choral music for the Chapel Royal and Westminster Abbey. Hear my prayer, O Lord (c. 1682) seems to have been conceived as part of a larger work that was never finished. In the original manuscript, the barline at the end is written without the usual flourish Purcell used to sign off complete works, and there are several pages left blank afterwards. Yet what we are left with, even without any larger framework, is a highlight of Purcell’s output. This setting of words from Psalm 102 is for eight voice parts, which Purcell uses to great effect, steadily building the texture from a simple opening to increasingly rich, plangent writing – resulting in such exquisitely haunting harmonies that the work well supports Benjamin Britten’s statement: “I had never realised before I first met Purcell’s music that words could be set with such ingenuity, with such colour.”

Purcell also wrote a number of Funeral Sentences: ‘Man that is born of a woman’ and ‘In the midst of life we are in death’, and, from his Music for the Funeral of Queen Mary, ‘Thou knowest Lord the secrets of our hearts’, which was performed during Queen Mary’s funeral in March 1695 – a few months before Purcell’s own death in November of the same year. ‘Thou knowest Lord’ is among the most cherished works in the choral canon, Purcell’s judicious use of chordal textures and repetition creating a work of timeless solemnity. Later in the programme, we hear Purcell’s setting of a Latin paraphrase of Psalm 3, Jehova, quam multi sunt hostes (c. 1680).

Henry Purcell (1658–1695)

© National Galleries of ScotlandDuring his time in Leipzig, Johann Sebastian Bach generally wrote motets for special occasions such as funerals; six of his surviving motets were catalogued as BWV 225-230. Der Geist hilft unsrer Schwachheit auf, BWV226 for double choir, was composed in 1729 for the funeral of a man described by Bach in the dedication as ‘the blessed Rector, Professor Ernesti’ – a professor of poetry at Leipzig University and director of the Thomasschule, where Bach worked. The music reflects a text from Romans, chosen by Ernesti, with vivid effects used to evoke the Spirit, and sighing figures for ‘unutterable sighs’, while learned fugal writing seems a fitting tribute to the academic to whom he was paying tribute.

Bach’s extraordinary Singet dem Herrn ein neues Lied, BWV225 (1727) is also in three movements, the outer sections to texts from Psalms 149 and 150. In the ambitious first movement, the main theme is separated by contrasting episodes (‘ritornello form’). In the central movement, the second choir sings words from the Lutheran chorale Nun lob, mein Seel, den Herren, answered by the first choir singing words derived from the chorale text. The work culminates in an irresistible four-part fugue starting at ‘Alles was Odem hat’: ‘All that have voice, praise the Lord!’

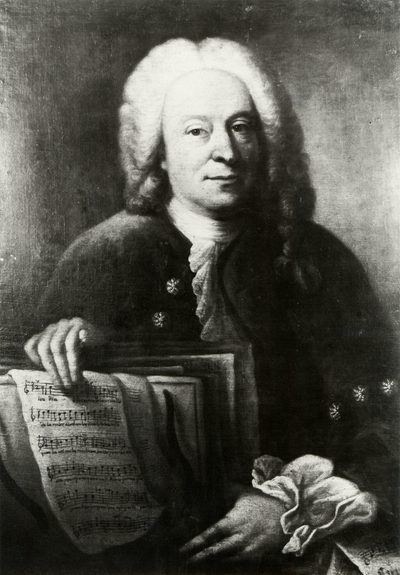

Johann Christoph Bach (1642–1703)

© Lebrecht Music Arts BridgemanJohann Christoph Bach was probably the most significant Bach before Johann Sebastian, described as being “as good at inventing beautiful thoughts as he was at expressing words”, his style “uncommonly full-textured". Johann Sebastian Bach referred to him as ‘the profound composer’. Johann Christoph’s motets epitomise the central German tradition inherited by his younger cousin; he studied with one of Schütz’s students, Jonas de Fletin, so his music represents a bridge between the pivotal styles of Schütz and Johann Sebastian Bach. His motets, though difficult to date precisely, seem to evolve from the use of clear distinctions between different choral textures, to a more fluid style. Ach, dass ich Wassers gnug hätte is a profoundly moving countertenor lament based on texts from Jeremiah, Psalm 38 and Lamentations, and features solo violin in support of the expressive vocal writing.

Handel’s Dixit dominus (1707) dates from his time in Italy and is likely to have been commissioned by one of his patrons there, Cardinal Carlo Colonna. It is his earliest surviving autograph manuscript. A psalm setting in Latin, this is a wonderful early instance of Handel’s aplomb when handling large-scale forms. In this vigorous setting for five soloists, five-part chorus, strings and continuo, he relished every opportunity for “word painting” – when the music vividly illustrates the text through its shape or sound. There’s the percussive setting of ‘conquassabit’ to represent shaking and shattering skulls; the use of intricate interwoven lines for ‘Tu es sacerdos’ (‘you are a priest’); and the unusual harmonies, interwoven lines and evocative chanting of ‘De torrente’, when the words, “He shall drink of the brook … therefore shall he lift up his head” defy easy illustration – but Handel somehow manages it anyway.

© Joanna Wyld, 2025

The modern composer builds upon the foundation of truthClaudio Monteverdi